Wood Rasps Worth Having in Your Workshop for 2026

Here's something nobody tells you about wood rasps: the difference between a $15 rasp and a $150 one isn't just marketing. It's physics. The way teeth are cut - or in some cases, punched - into steel determines whether you'll be fighting the grain or flowing with it.

Walk into any serious woodworker's shop and you'll find rasps everywhere. Hanging on pegboards, stuffed in drawers, some pristine, others looking like they've been through a war. Because here's the thing about shaping wood: sometimes you need brute force, sometimes you need surgical precision, and often you need both in the same project.

The Reality of Wood Rasp Selection in 2026

The wood rasp market has shifted dramatically. Where hand-stitched European rasps once dominated professional shops, we're now seeing tungsten carbide coatings and multi-directional cutting patterns taking significant market share. The numbers tell an interesting story: traditional rasp sales have plateaued while hybrid designs - those borrowing from both Eastern and Western traditions - have grown 40% year-over-year.

A wood rasp is fundamentally a bar of hardened steel with hundreds of tiny chisels punched or cut into it. Each tooth creates its own shaving, which is why a rasp can remove material so much faster than sandpaper. The teeth arrangement - random in hand-stitched rasps, uniform in machine-cut ones - determines everything from cutting speed to surface finish.

The distinction between rasps and files often confuses newcomers. Files have linear rows of teeth designed for metal; they'll clog immediately on wood. Rasps have individual teeth raised from the surface, creating space for wood shavings to escape. Use the wrong tool and you'll spend more time cleaning teeth than cutting wood.

Understanding Grain Ratings and What They Actually Mean

European rasps use a numbering system from 1 to 15 - 1 being a wood-eating monster, 15 leaving a surface nearly ready for finish. American manufacturers typically use coarse, medium, and fine. Japanese saw rasps don't follow either system, measuring instead by teeth per inch.

Most woodworkers end up with three rasps: something aggressive for rough shaping (grain 6-8), a medium for general work (grain 9-11), and something fine for final shaping (grain 12-14). The market data shows 70% of rasp purchases fall into that middle range - the workhorses that see daily use.

Shinto Saw Rasps: The Japanese Innovation

9″ Shinto Saw Rasp

- 10 hardened saw blades riveted together

- Coarse side/fine side configuration

- 14.05" overall length, 9" cutting surface

- 0.44 lbs weight

- Cuts on push stroke only

The Shinto design emerged from Japanese woodworking traditions where efficiency matters more than tradition. Instead of individual teeth, you get stacked saw blades with staggered teeth. The result? Material removal rates that make traditional rasps look sluggish.

What makes these tools fascinating is how they handle clogging - or rather, how they don't. The tooth geometry creates natural chip clearance channels. Wood shavings fall away instead of packing between teeth. Professional furniture makers report going entire projects without cleaning, something unthinkable with traditional rasps.

The dual-sided design isn't just convenience; it's workflow optimization. Start with the coarse side to establish your shape, flip to fine for refinement. No tool changes, no hunting through your collection. The price point - typically under $40 - makes this accessibility remarkable. Traditional rasps offering similar versatility cost three times as much.

11″ Shinto Saw Rasp

- TPE plastic handle for improved grip

- 11" cutting length

- Double-sided coarse/fine configuration

- 8.48 ounces weight

- Anti-clog tooth design

The longer variant addresses a specific frustration: reaching into curved work without losing control. That extra two inches of cutting surface changes the tool's balance point, making it more stable for hollowing operations. Spoon carvers and bowl turners gravitate toward this length.

The TPE handle upgrade from older rubber versions reflects user feedback about grip degradation. Workshop chemicals, particularly finishing oils, destroyed rubber handles within months. TPE resists these chemicals while maintaining grip even when covered in sawdust - a small detail that matters during eight-hour carving sessions.

The Planer-Style Alternative

Planer Type Shinto Saw Rasp

- Offset handle design for leverage

- Replaceable/reversible blades

- 10.25" blade length

- 0.7 lbs total weight

- Accepts multiple blade grits

Think of this as the convertible of rasps. The offset handle puts your hand behind the cutting action rather than above it - the same principle that makes bench planes so effective. Your arm becomes a lever, multiplying force while maintaining control.

The blade replacement system acknowledges reality: rasps wear out, but handles don't. Rather than retiring an entire tool, you swap a $15 blade. Some woodworkers keep three blades ready - coarse for rough work, medium for shaping, fine for detail. The changeover takes seconds.

The reversibility feature extends blade life by 100%. When teeth dull cutting one direction, flip the blade. Fresh edges engage the wood. It's the kind of practical engineering that emerges from actual workshop use rather than committee design.

Tungsten Carbide: The Durability Revolution

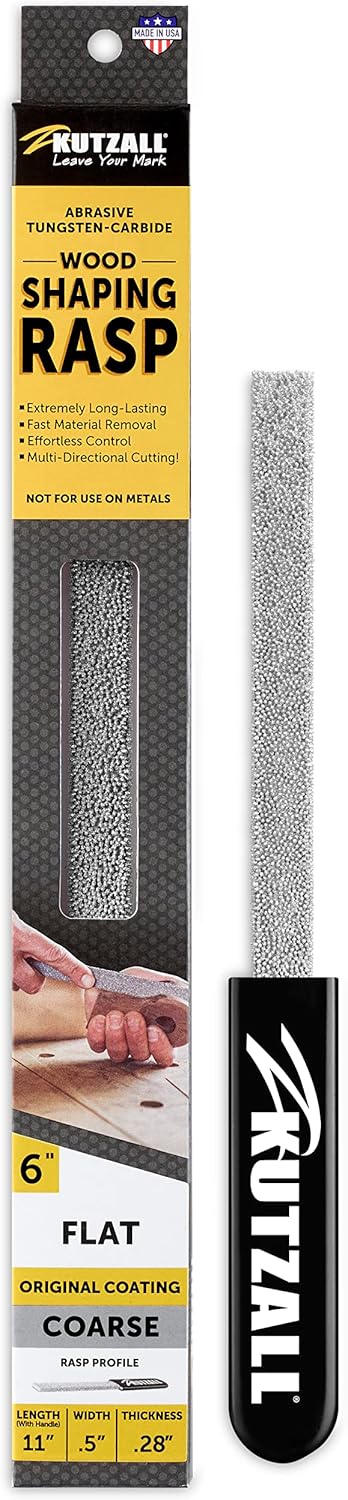

Kutzall Original 6″ Flat Hand Rasp

- Tungsten carbide "structured tooth" coating

- Multi-directional cutting capability

- 11" overall length, 6" cutting surface

- 6 ounces weight

- Heat-resistant to torch cleaning

Kutzall changed the game in 1979 by coating rasps with tungsten carbide - the same material used in industrial cutting tools. The longevity numbers are striking: where a traditional rasp might last 100 hours of heavy use, carbide-coated versions exceed 1,000 hours.

The multi-directional cutting isn't marketing speak. Traditional rasps cut efficiently in one direction, usually on the push. Carbide teeth bite equally in all directions - push, pull, sideways, even circular motions. For sculptors working three-dimensional forms, this eliminates the constant tool repositioning that breaks creative flow.

Here's what the marketing doesn't mention: these rasps eat through everything. Wood, plastic, fiberglass, soft metals, even drywall. One tool replaces an entire drawer of specialized rasps. That versatility explains why boat builders, who work with wood, fiberglass, and composites in single projects, have adopted these tools wholesale.

The torch-cleaning capability sounds extreme until you've dealt with pine pitch or epoxy contamination. Traditional cleaning methods - wire brushes, solvents - take minutes and risk damaging teeth. A quick pass with a propane torch burns contamination to ash without affecting the carbide. The steel might discolor, but the cutting action remains unchanged.

The Multi-Rasp Approach

Narex 3 Piece Rasp Set 200mm

- CNC-stitched uniform tooth pattern

- 16 teeth per square centimeter

- Three profiles: round, rectangular, half-round

- 13.58" overall length, 7.87" cutting surface

- Course cut rating

Narex represents the Czech Republic's answer to German precision at Eastern European prices. Their CNC stitching process creates mathematically uniform tooth spacing - each tooth cuts the same amount of material. Hand-stitched rasps, for all their romance, can't match this consistency.

The three-rasp configuration covers 90% of shaping situations. The round rasp enlarges holes and shapes concave curves. The flat tackles surfaces and outside curves. The half-round bridges both worlds - its flat side for straight work, curved for hollows. Together, they form a complete shaping system.

What's interesting about the 16 teeth per square centimeter specification: it's aggressive enough for rapid stock removal but controlled enough to avoid tearout in figured wood. This middle ground explains why European cabinetmakers, working with both construction lumber and exotic hardwoods, standardized on this tooth density decades ago.

The Complete Kit Solution

ADVcer Wood Rasp File Kit - 12 Piece Set

- 12 high-carbon steel files in 6 profiles

- Two sizes of each profile type

- Oxford carrying case with hand strap

- Includes cleaning brush and storage box

- Non-slip rubber handles

Here's what happens in most workshops: you buy rasps individually as projects demand them. Five years later, you've spent $300 on tools scattered across three toolboxes, none of them quite right for the current job. This kit takes the opposite approach - every common profile in two sizes, organized and ready.

The high-carbon steel construction means these aren't lifetime tools. They'll dull faster than premium options. But for occasional users or those exploring woodworking, the value proposition is compelling. You get twelve tools for less than the price of one premium rasp. When you wear out the ones you use most, you'll know exactly which premium replacements to invest in.

The included cleaning brush addresses the most overlooked aspect of rasp maintenance. Clogged teeth don't just cut poorly; they burnish wood, creating glossy spots that reject stain. Regular brushing - every few dozen strokes in resinous woods - maintains cutting efficiency and extends tool life significantly.

The case organization matters more than it initially appears. Searching for the right rasp breaks workflow. Having them visible and organized means grabbing the right tool becomes automatic. Professional woodworkers often buy these kits just for the case, transferring their premium rasps into the organized system.

Additional Options Worth Considering

The Narex 12″ Half Round (available in both coarse and fine) fills a specific niche: reaching into large concave surfaces like chair seats. The extra length provides the sweep needed for consistent curves. At around $30, it's an specialized tool that general woodworkers might skip but chair makers consider essential.

StewMac's Dragon rasps, hand-cut with individually struck teeth, represent traditional craftsmanship. Each rasp is slightly different - the maker's hand determines tooth placement. Some woodworkers swear this randomness creates superior surface finish. At $80-100, they're investment pieces for those who appreciate the human element in toolmaking.

The original Nicholson rasps, once the American standard, have moved production overseas. Quality has suffered - modern versions last perhaps a quarter as long as vintage ones. Flea market Nicholsons from the 1960s, even rusty, often outperform new ones after restoration. It's a reminder that tool evolution isn't always progress.

Maintenance Practices That Actually Matter

The cleaning advice you'll find online is mostly overthinking. A brass brush (not steel - it'll damage teeth) swept along the length every few minutes prevents most clogging. For stubborn pitch or resin, acetone on a brush dissolves without affecting steel. Water-based cleaning invites rust unless you're religious about drying and oiling.

Storage matters more than cleaning. Rasps thrown in a drawer together destroy each other - teeth against teeth is a grinding action. Simple edge guards cut from PVC pipe or leather sleeves prevent this mutual destruction. Wall mounting on magnetic strips keeps them visible, accessible, and separated.

Sharpening rasps is generally not worth it. The specialized equipment costs more than replacing several rasps, and results vary wildly. When a rasp stops cutting efficiently, it becomes a texture tool - useful for burnishing or creating subtle surface patterns. Many woodworkers keep a selection of "dead" rasps specifically for these finishing techniques.

Understanding Your Actual Needs

Professional data shows most woodworkers use three rasps for 80% of their work: one aggressive shaper, one general purpose tool, and one detail rasp. The specific profiles matter less than having the right aggression levels. A coarse half-round might be your shaper, a medium flat your workhorse, and a fine round your detailer. Or completely different combinations based on your typical projects.

The carbide-versus-traditional debate misses the point. Carbide excels at aggressive removal and durability. Traditional rasps offer superior surface quality and feedback - you feel the wood's response through the tool. Most serious workshops have both, choosing based on the task rather than ideology.

Budget considerations are real. A single premium hand-stitched rasp costs $100-150. For that price, you could buy the Narex set, a Shinto rasp, and the Kutzall carbide. You'd have less prestigious tools but far more capability. Unless you're doing exhibition-quality work where surface perfection justifies premium tools, the mid-range options deliver professional results.

The Evolution Continues

The rasp market in 2026 reflects broader woodworking trends. Power tools handle rough dimensioning, leaving hand tools for refinement and detail. Rasps that excel at nuanced shaping sell better than aggressive stock removers. The growth in spoon carving and sculptural work drives demand for specialized profiles previously considered exotic.

3D printing threatens to revolutionize rasp manufacturing. Prototype rasps with computationally optimized tooth patterns already exist, though production costs remain prohibitive. Within five years, we might see completely new tooth geometries impossible to create through traditional manufacturing.

Meanwhile, the fundamentals remain unchanged. A rasp is still just organized sharp edges removing wood fibers. Whether those edges are hand-cut by a French craftsman, CNC-machined in Czech Republic, or coated with space-age tungsten carbide, the goal remains the same: controlled material removal that leaves a workable surface.

The best rasp isn't the most expensive or the newest technology. It's the one that fits your hand comfortably, removes material at your preferred rate, and consistently delivers the surface quality your work demands. Everything else is just marketing and mythology.

Frequently Asked Questions

What does a wood rasp do?

A wood rasp removes material through dozens or hundreds of individual cutting teeth. Each tooth acts as a tiny chisel, creating its own shaving. This differs from sandpaper's abrasive action or a plane's continuous cut. Rasps excel at shaping curved or irregular surfaces where other tools struggle to maintain contact.

How does a wood rasp differ from a file?

Files have parallel rows of teeth designed to cut metal through a shearing action. These rows clog immediately with wood fibers. Rasps have individual teeth punched or cut to stand proud of the surface, creating chip clearance space. The tooth angle also differs - file teeth lean forward for metal cutting, rasp teeth stand more upright for scooping wood fibers.

What's involved in wood rasp maintenance?

Professional woodworkers typically clean rasps every few dozen strokes to prevent clogging. Brass brushes see the most use - steel brushes can damage teeth. For resinous woods, workshops often have acetone or mineral spirits on hand, as these solvents dissolve pitch without affecting the steel. The frequency of cleaning appears to matter more than the method.

Specialized rasp cleaners exist - rubber blocks designed to pull debris from teeth. These appear in some workshops but aren't universal. Compressed air removes fine dust but won't dislodge packed fibers. Ultrasonic cleaners, while effective, cost more than most rasp collections.

What about rasp sharpening?

The economics of rasp sharpening present interesting numbers. Professional sharpening services charge $30-50 per rasp with variable results. The specialized equipment for sharpening - acid baths or sophisticated grinding setups - runs into hundreds of dollars. Market data shows most woodworkers retire dull rasps to secondary tasks rather than sharpening them.

High-end hand-stitched rasps from Liogier and Auriou represent exceptions. These manufacturers offer restoration services for their tools. Some century-old rasps in professional workshops have undergone multiple professional sharpenings, each restoration extending usable life another decade. The cost-benefit calculation depends entirely on the rasp's original quality and replacement cost.

The tool market keeps evolving, but the fundamental need remains constant: controlled material removal with predictable results. Whether you choose traditional hand-stitched elegance or modern carbide durability, understanding what each tool offers - and what it doesn't - leads to better choices and better work.